Teachers with a Lancet—An Extra-ordinary Tale of Innovation

Save the Children Director for Health in Malawi, David Melody, recently visited Malawi’s south eastern district of Zomba where he saw how innovation is bridging schools and health centres; teachers and health workers. He reports.

“Innovation!” “Out of the box thinking!” “Creativity!” “Blue sky thinking!” There are many buzzwords – in international development, global public health and other domains – signposting the search for initiatives, which are novel, different, out of the ordinary. Yet much of the time we remain inhibited by norms and conventions, constrained by the status quo, largely unable to turn the quest to think outside of the box from noble aspiration to practical reality.

While jolting over a rutted dirt road out of Zomba, in south-east Malawi, I wasn’t particularly expecting to witness innovation at close quarters. The area is poor: children wander about barefoot, people break their backs to bring in the meagre maize harvest, and essential infrastructure is run down or entirely lacking, schools and health centres running on shoestring budgets. It’s hardly the kind of place associated with cutting-edge innovation – MIT, say, or Silicon Valley. And yet here in this far-flung corner of central Africa innovation is bringing about amazing changes for children.

I was here to visit Chikala School, part of a study being run in partnership between Save the Children, the Ministries of Health and Education, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Malaria Alert Centre of Malawi’s College of Medicine; it’s funded through the sponsorship programmes of Save the Children US and Italy and, for the evaluation, by 3ie. In essence the study is addressing the challenge of bringing together two separate boxes, health and education, in a way that keeps children healthy and learning at the same time. This may sound straightforward, but it’s no easy task: sectoral ways of working are very ingrained, while even the public sees things in black and white – teachers are there to teach, health workers to treat. But when a child is sick, and her family has no means of transport, and it’s 15 kilometres to the nearest health centre, and the dirt road is impassable in the rainy season, then conventional ways of thinking are no longer good enough – the child that has malaria struggles to get treatment, staying at home sick as their health and education fall by the wayside, often for good. So, building on previous efforts to address malaria in schools, the study partners – led by the Ministry of Health – decided to investigate how feasible it would be to train teachers to both diagnose and treat malaria.

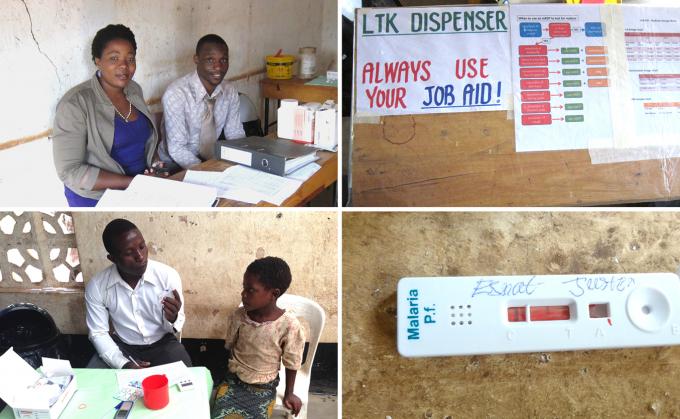

Bottom: 8-year-old Esnat having a malaria test done by her grade 2 teacher

I was greeted by Memory Gobola, a teacher at the school. Only Memory is no longer just a teacher – she’s now also a “dispenser”. She took me to the dispensary, a room at the end of a block of classrooms. It was basic but functional – a few tables and chairs, awareness-raising posters on the wall, and the essentials – malaria rapid diagnostic tests, anti-malarials and other supplies. What was far from merely functional was the passion with which Memory described the situation before and after the study, and how the role of the teacher-dispensers was absolutely central to the positive changes which had taken place: “So many children used to miss school with fever, even those that stayed were unable to concentrate in class, and some who left never returned. We teachers felt so powerless – we have such a big role to play in the development of these children yet when a simple mosquito bite ended their education we were unable to do a thing”. Memory’s fellow dispensers, Macloud Kumasinga and Lucina Makumba, described with enthusiasm how after just a week’s training they were able to diagnose and treat malaria, and how quickly they started to see the difference: “On a typical day in the rainy season around 40 children show up sick, many are unable to stand, some are vomiting, all of them are weak with fever, it’s truly awful. Then the tests show that maybe 35 of them have confirmed malaria, so we give them treatment immediately and many of them are recovering within hours, and often they are back in class and active the very next day!” Children with fever but not malaria are given paracetemol and referred to the health centre – while it may be some distance, referral forms and the teacher-dispensers’ vigilance helps to ensure that they do actually go. Crucially too, recognition of this health and education revolution is becoming widespread in the communities around the schools in the study – Macloud was full of justifiable pride when he told me: “Families really appreciate what we are doing for the health of their children – as teacher-dispensers we really have a lot of respect from people in the community. Some almost see us as miracle workers, they even want to bring us their children with all sorts of other ailments!”

Of course not everything is straightforward. The dispensers’ workload can be very high, often causing them to miss class – they rely on the benevolence of their fellow teachers to cover for them, a generosity of spirit, which can’t be taken for granted, especially with an average of 80-100 children per class. The paperwork can be too much – “We are teachers, health workers and accountants!” Memory told me; the trips to the health centre to get resupplies often arduous; and very few families have bednets at home, which would stop children getting malaria in the first place. But issues like these are to be expected when trying something new, something different, something innovative, and it is the job of the partners working on the study to find solutions – for getting it right would mean that this incredibly powerful intervention would be made available to schoolchildren across Malawi.

As I listened to Memory, Macloud and Lucina, it was impossible not to feel moved at their incredible commitment, their deserved sense of pride almost glowing through the grey Zomba morning – and all for no other reward than the gratitude of the children and their families and their own sense of satisfaction at the difference they’re making. And as I listened, another development buzzword occurred to me, another overused term that is elusive to put into practice, yet was standing right here in front of me – these three passionate teacher-dispensers were the embodiment of empowerment.

Written by,

David Melody, Director of Health

Malawi

Malawi